18/08/2014 13:45

The Whole Wide World. ‘Tiny Creatures’ and ‘If . . .’

If you want to find the wildly creative people now, I’m told, look in fields that have to do with science, math and technology. They say these days, that’s where an imagination can really fly. I’ve been skeptical. Growing up as a creative type, I experienced a plummeting sensation just catching a whiff of formaldehyde outside the science lab, or hearing the word “cosine,” which to me had a sinister ring. I couldn’t see science and math as anything other than earthbound and rote, and yet all too often, confusingly abstract.

Two new picture books may make me a believer. Both aim to help children comprehend proportion and scale — or, as I am now inspired to put it, the vastness and majesty of the universe. They do so with playfulness and visual style, obliterating distinctions between a “creative” and a “fact-based” storybook. Both these books pulled me into their worlds as magically as any fictional narrative might.

In “Tiny Creatures: The World of Microbes,” aimed at younger children, the British children’s author Nicola Davies (“Just Ducks!”) sings the praises of microorganisms, calling attention to the staggering discrepancies between size and impact. “You know about big animals, and you know about small animals,” the book begins, “but do you know that there are creatures so tiny that millions could fit on this ant’s antenna?”

And wow, do they reproduce fast! They can double in number every 20 minutes. So on one page we see a microbe illustrated at the size of a grain of rice. Just 11 1/2 hours later, there are enough of them to fill a whole large-format page, and 20 minutes after that, enough to cover an entire double-page spread, arranged by the illustrator, Emily Sutton, into quite a lovely pattern. By the end of the book, Davies and Sutton have beautifully made the case that microbes are “the invisible transformers of our world — the tiniest lives doing some of the biggest jobs.”

Both Davies’s tone and the charming retro-ish watercolor illustrations by Sutton seem likely to please young children by balancing repetition and flights of fancy. Many of the pages feature the same freckle-faced girl and boy. To show that microbes can eat anything, the pair sit at a table displaying a side of ham, a bowl of rocks and a cat. When we learn that there are possibly a hundred times more microbes living in your stomach than there are people on Earth, they look down gravely at their bellies. “Don’t worry!” Davies writes. Some make you sick, but “the ones that live in you and on you all the time help keep you well.”

David J. Smith’s “If . . . : A Mind-Bending New Way of Looking at Big Ideas and Numbers” suffers only from a case of subtitle gigantism (in publishing, usually an adult-onset affliction). What he’s doing is not completely new, and while many children and adults are indeed likely to find it “mind-bending,” do we really need to be prompted like that on the cover? But that’s a quibble, because once open, this is one of those books school-age children can happily page through many times, and even adults may find themselves taking a second and third whirl.

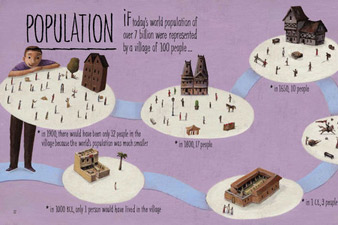

Each two-page spread takes up something whose size or number is so big, it’s hard to swallow whole. Smith converts it into something else that’s part of our everyday understanding, rendered in detailed but slightly smudgy whimsical-realist illustrations by Steve Adams. One page shows a waiter holding a tray of water glasses. “If all the water on Earth were represented by 100 glasses,” Smith writes, “97 of the glasses would be filled with salt water”; only three would be fresh water, and only one would be accessible to people. Other interesting facts about humans’ use of water tumble down a sidebar.

Several spreads cleverly capture time and history. A calendar shows that if the events of the last 3,000 years were condensed into one month, the Great Wall of China would be built on Day 8, the dodo would go extinct on Day 27 and the first computer would arrive on Day 30. Others illuminate life expectancy, energy sources and the distribution of wealth (through piles of coins: One person, representing the richest 1 percent, stands on a pile of 40 coins; on the other side of the spread, 50 people stand on just one coin).

I’m woefully late to this STEM-field party, I know. But among the pleasing ideas these books have provided is the image of a generation of children — creative types, all of them — who have picture books like these on their shelves.